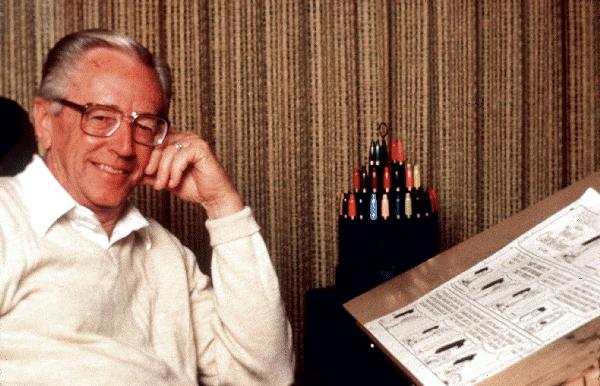

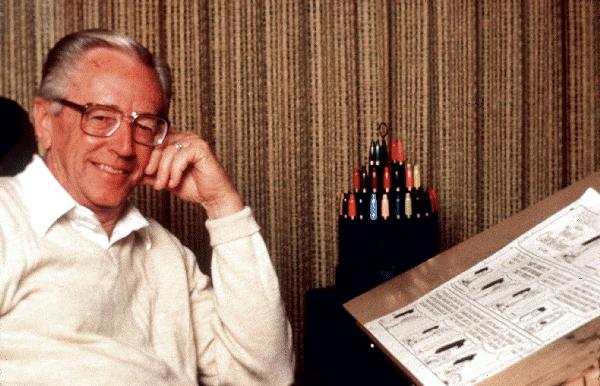

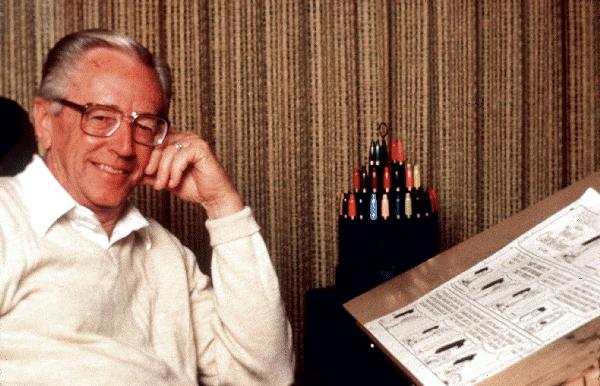

Charles Schulz poses with his drawing board in this undated photo released in New York on December 14, 1999. (The Associated Press photo/United Media)

And responds...(page 7)...

More news from the media world...

So Long, Snoopy & Co.

For 50 years, `Peanuts' has tickled America's funny bone. But more than that, Charles Schulz's characters mirrored our lives and taught us timeless lessons about faith, hope and love. You were a good man, Charlie Brown.

January 1, 2000

By Sharon Begley

Newsweek

It was, all in all, a typical few days for the "Peanuts" gang.

Linus, having built a lopsided snowman, quietly instructs his creation, "Don't slump..." Sally has trouble sending her teacher a Christmas card because she doesn't know her name; when Charlie Brown asks what she says when called on in class, Sally responds, "Who, me?" Snoopy, leaning over the typewriter atop his doghouse, writes the scene in his novel where one dogwalker touches another's cheek, and the dog thinks, "Sooner or later, one of them is going to forget and drop the leash." And on Sunday, as Snoopy and Woodstock trudge through the snows of Valley Forge, they reach the Delaware just as Washington pushes off. "Rats! We're too late," says Snoopy. "I was hoping we could get a ride into town."

A sense that the great events of history are passing one by. A dream of liberation. The ability to be at peace despite abject cluelessness. A plea for things to right themselves. Last week brought, in other words, the usual sweetly melancholic depiction of the human condition from the pen of Charles M. Schulz that the previous 2,500-plus had.

But for fans, the latest strips were seen through a glass darkly, for Schulz had pulled the oldest trick in the cartoonist's book: He had proclaimed that, after almost 50 years, "the end is nigh." It was no joke. Schulz, already suffering from Parkinson's disease, had several small strokes in November and underwent emergency surgery, during which doctors diagnosed colon cancer. Hardly able to draw, he announced that there would be no new daily "Peanuts" strips after Jan. 3, and no new Sundays after Feb. 13.

Good grief.

We don't mean to sound like a doctoral dissertation (though "Peanuts" has been the subject of learned treatises invoking semiotics, Adler and Freud). But let us point out that those who mourned the imminent passing of Charlie Brown and his gang weren't upset solely at the prospect of one daily chuckle fewer in their lives. For many of its 355 million readers around the globe (the world's most widely read comic strip, it appears in 2,600 newspapers in 75 countries and 21 languages) "Peanuts" touches something much deeper than the funny bone. It embodies a world where first innings last so long the outfield goes home for lunch, where "the meaning of life is to go back to sleep and hope that tomorrow will be a better day," where beagles writing the great American novel struggle to get past "It was a dark and stormy night."

"Peanuts" was born with the baby boomers and the suburbs, into a time when Americans, flush with victory and prosperity, could afford to see childhood as a separate stage of development. The strip may not depict a typical childhood, exactly -- it is the rare suburb whose tots' favorite film is "Citizen Kane" and whose pets plan D-Day -- but that hardly mattered. It offers an affirmation of childhood as what Dostoevsky, in "The Brothers Karamazov," called a "sacred memory." Before "Peanuts," most strips featuring children "were about mischievous kids pulling gags on their parents," says Mort Walker, creator of "Beetle Bailey." "Schulz gave us a realistic childhood with all its losses and rejections. His kids had pathos." Like Oskar in "The Tin Drum," the children never age. But then, they don't have to. They already suffer from adult disillusionment, failure and self-doubt. (Adults themselves are never seen; when heard, they speak in a honking squawk.)

This cross-generational appeal helps explain why, although boomers grew up with "Peanuts," their children turn to it, too. The off-Broadway musical "You're a Good Man, Charlie Brown," which debuted in 1967, was revived in February 1999, and the Emmy-winning "A Charlie Brown Christmas" has run every year since 1965. The strip inspired four feature films, three amusement parks and books that have sold a total of 300 million copies.

Sometimes I lie awake at night, and I ask, "Why me?" Then a voice answers, "Nothing personal. Your name just happened to come up."

Older fans have no trouble identifying with Charlie Brown's nocturnal epiphanies about cosmic angst, or seeing in the children the foreshadowings of what they themselves would become. "The poetry of these children arises from the fact that we find in them all the problems, all the sufferings, of the adult," Italian novelist Umberto Eco wrote in The New York Review of Books in 1985. Kids, of course, are oblivious to all of this. They simply smile in agreement when, after a 63-0 first inning, Linus says sadly to Charlie Brown, "There goes our shutout."

Schulz, a devout Christian, imbues "Peanuts" with gentle lessons in faith, hope and charity. Is there a faith greater than Charlie Brown's that Lucy will, this time, hold the football in place? The strip has cited the Book of Job; in the Christmas special, Linus gives a heartbreaking recitation from Saint Luke's Gospel. More often, though, the "Peanuts" gospel means lessons in life. As cartoonist Bill Mauldin once put it, "Love thy neighbor even when it hurts. Love Lucy." And don't expect the twists of fate to change eternal verities.

After 43 years, Charlie Brown hit a home run. His angst remains.

I thought I had life solved. But there was a flag on the play.

Although the place is clearly an America of coed sandlot baseball, the time is ... well, it is every time in the postwar era and it is no time. In "Peanuts," the '60s never happened; neither did Vietnam or Watergate or Monica. The only reflections of the times are subtle, like the 1968 introduction of Franklin, Charlie Brown's black friend. And Woodstock has been using a cell phone lately.

Like Charlie Brown, Schulz, too, showed an early talent for snatching defeat from the jaws of victory. Born in Minneapolis in 1922, "Sparky" Schulz once showed up at a movie theater that was promising free Butterfingers to the first 100 customers. Schulz was the 101st. His high-school yearbook never ran the drawings a teacher invited him to submit. At 17 Schulz enrolled in art correspondence school (receiving his lowest grade in drawing children), but his studies were interrupted by World War II. Schulz served as an infantryman before working his way up to staff sergeant and leader of a machine-gun squad. While in the service, he drew emotional sustenance from Mauldin's Willie and Joe cartoons. Every Veterans Day since the 1980s, Snoopy announces that he is going to "quaff a few root beers" with Mauldin.

After the war Schulz worked as an instructor at the correspondence school, and there he fell in love with the red-haired Donna Johnson in accounting. But Johnson married another (Schulz explained her choice as a result of her mother's belief that he would never amount to much). Thus was born Charlie Brown's unrequited love for The Little Red Haired Girl.

In 1948 Schulz sold a single-panel comic called "L'il Folks" to the St. Paul Pioneer Press. When the paper refused to run it more than once a week, he offered it in 1950 to United Feature Syndicate, which promptly changed the name to "Peanuts," which Schulz still hates. Since then Schulz has drawn every line, inked every background, lettered every dialogue bubble on seven strips a week. It is an astounding output ... more than 18,000 strips. "The majority of cartoonists, especially ones who've been drawing for a long time, have gang writers, people who draw the background and often people who actually do the artwork," says editorial cartoonist Mike Luckovitch. "Sparky was never like that."

Colleagues see Schulz as an almost mythic figure in the history of cartooning. Garry Trudeau, writing in The Washington Post, called "Peanuts" "the first (and still the best) postmodern comic strip. It was populated with complicated, neurotic characters speaking smart, haiku-perfect dialogue."

Cathy Guisewhite, creator of "Cathy," said that "a comic strip like mine would never have existed if Charles Schulz hadn't paved the way. He broke new ground, doing a comic strip that dealt with real emotions, and characters people identified with."

I was jumping rope ... everything was all right ... when ... I don't know ... suddenly it all seemed so futile!

"Peanuts," like any great work of art, can be read on many levels. For every child who giggles over Sally's jump-rope troubles or Snoopy's slam-dunking a doughnut into a cup of coffee, an adult nods at the strip's tragicomic view of life. "I have deep feelings of depression," Charlie Brown confides in a 1959 strip. "What can I do about it?" "Snap out of it," Lucy replies. In the 1960s, Charlie Brown exults at the prospect of finally flying a kite that won't be eaten by a tree ... until he pauses and tells the foliage, "Here, take it. It's been a long winter, and I'm very tender-hearted."

Happiness is a warm puppy.

"Peanuts" is (we refuse to say "was") infused with an almost quaint optimism, one that tiptoed all the way up to unrequited hope. It was Linus's hope that this time the Great Pumpkin would visit, Lucy's that this time Schroeder would notice her. As sociologist Paul Schervish of Boston College describes it, "Expectation and aspiration never cease, but are... ever foiled." Yet if the characters' faith in a better future is quintessentially American, it travels well.

"Peanuts" merchandise, starting with a six-inch plastic Snoopy in 1958, now includes toys, videos, clothing, Hallmark cards, sheets, MetLife ads and ... well, more than $1 billion in sales every year. If the "Peanuts"-ing of the world seems crassly exploitative to some critics (even one United Media insider says it "casts a mercantile pall over something innocent"), it's because Schulz can't say no. It is as if Schulz -- who worries that promised TV interviews will be canceled once people realize how unworthy he is -- thinks spurning a deal would tempt fate.

You kind of like me, don't you Chuck?

Schulz chose to retire, he told Newsweek at his rambling home in the hills above Santa Rosa, California, because "all I care about now is tomorrow; I want to feel better tomorrow." The ideas do not come anymore, and since his strokes he often struggles to find the right expression. "Words are just gone," he says. But although Schulz has laid down his pen, "Peanuts" will go on: United Media will re-run old strips, from 1974 forward. And so Schroeder will still play "Fur Elise" and Pig Pen will be trailed by the dust of history and Charlie Brown's costume for Halloween will have eyeholes everywhere but over his eyes. Fans will still open the paper with the faith of a Charlie Brown running up to the football.

But Charles M. Schulz will no longer be whisking away new footballs.

With Yahlin Chang, Peter Plagens and Devin Gordon in New York, Mark Miller in Santa Rosa and bureau reports

Schulz bids goodbye in last new daily "Peanuts"

January 1, 2000

By Melissa Jordan

Nando Media/The Associated Press

SAN FRANCISCO -- In the last new daily "Peanuts" strip set to run in newspapers on Monday, Snoopy looks over a farewell message from creator Charles Schulz.

Schulz, 77, who has written, drawn, colored and lettered every "Peanuts" strip for almost 50 years, decided to retire after being diagnosed with colon cancer in November. His contract stipulates that no one else will ever draw the comic strip.

The single-panel farewell strip is primarily a text message, over Schulz's signature, with the Snoopy drawing in the lower right corner.

"Dear Friends," Schulz writes. "I have been fortunate to draw Charlie Brown and his friends for almost 50 years. It has been the fulfillment of my childhood ambition. Unfortunately, I am no longer able to maintain the schedule demanded by a daily comic strip, therefore I am announcing my retirement.

"I have been grateful over the years for the loyalty of our editors and the wonderful support and love expressed to me by fans of the comic strip.

"Charlie Brown, Snoopy, Linus, Lucy ... how can I ever forget them..."

Schulz's beloved cast of characters appear in 2,600 newspapers, reaching an estimated 355 million readers daily in 75 countries.

A final new Sunday strip by Schulz will run in newspapers on Feb. 13. After that, United Feature Syndicate will publish "Peanuts" reprints.

Schulz, who is focusing on his health and family at home in Santa Rosa, California, never expected the support he's be given by readers, who have sent him 400 to 500 pieces of mail a day, his secretary, Edna Poehner, said Friday.

"He just drew pictures. It's overwhelming for him," she said.

SCHULZ, SNOOPY BID READERS FAREWELL IN LAST DAILY 'PEANUTS'

Sunday, January 2, 2000

The Associated Press

SAN FRANCISCO -- Snoopy, perched on his doghouse in front of his typewriter, looks over a farewell message from creator Charles Schulz in the last "Peanuts" strip, running in newspapers Monday.

Schulz, 77, who has written, drawn, colored and lettered every "Peanuts" strip for almost 50 years, decided to retire after being diagnosed as having colon cancer in November. His contract stipulates that no one else will ever draw the comic strip, which appears in more than 2,600 newspapers in 75 countries.

The single-panel farewell strip is primarily a text message, over Schulz' signature, with the Snoopy drawing in the lower right corner.

"Dear Friends," Schulz writes. "I have been fortunate to draw Charlie Brown and his friends for almost 50 years. It has been the fulfillment of my childhood ambition. Unfortunately, I am no longer able to maintain the schedule demanded by a daily comic strip, therefore I am announcing my retirement.

"I have been grateful over the years for the loyalty of our editors and the wonderful support and love expressed to me by fans of the comic strip.

"Charlie Brown, Snoopy, Linus, Lucy . . . how can I ever forget them . . ."

A final Sunday strip by Schulz will run in newspapers Feb. 13. After that, United Feature Syndicate will publish "Peanuts" reprints.

Schulz, who is focusing on his health and family at home in Santa Rosa, California, never expected the support he's seen from readers, who have been sending him 400 to 500 pieces of mail a day, his secretary, Edna Poehner, said Friday.

"He just drew pictures. It's overwhelming for him," she said. "I take a bundle to him each day, and he can go through them as he feels up to it. It's unbelievable to him.

"For the most part, people are saying they're going to miss Charlie Brown, but 'you've earned the right to retire and enjoy other things.' The letters are beautiful."

YOU'RE A GOOD MAN, CHARLES SCHULZ

Sunday, January 2, 2000

By Ann Shields

Special to The Times

It's a slow week in the literary community as the new year begins. And it's a sad week for fans and admirers of "Peanuts" creator, Charles Schulz. As of Monday, he will retire his pen and ink, shifting his focus to his health and his family.

Drat! No more new woes for Charlie Brown, the world-famous cartoon character who never quite gets it right.

So why does this news matter to us? It matters, because his words are read in more homes than those of many literary giants.

Schulz, better know as Sparky to his friends, is our own friendly philosopher with the slightly bemused view of life. He also happens to be a friend.

When we first met it was June 1983, and the Santa Barbara Writers Conference was in full swing. Seated on a couch in the auditorium of the Miramar Hotel in Santa Barbara, Schulz asked where I was headed and invited me to sit down.

I got to hang out with him and his wife, Jeannie, then and for many conferences after that, no credentials required. He treated me to an ice cream cone once, his favorite treat. Another year, at a dinner with his family on Father's Day, Jeannie learned I could analyze handwriting. Everyone at the table scribbled samples to analyze. Schulz watched with a skeptical eye.

Last year he skipped the conference--not feeling well was the word. Since then, he learned he has colon cancer.

In December, UPS delivered his yearly Snoopy calendar with the usual holiday greeting from Sparky and Jeannie. A few weeks earlier, a heavier package

had arrived. It was his latest publication, "Peanuts--A Golden Celebration: The Art and the Story of the World's Best-Loved Comic Strip" by Charles M. Schulz (Harper-Collins, $45). It is vintage Schulz--an upfront and personal view of life before and after the creation of "Peanuts." Written in his easy conversational style, you read how Charlie Brown, Snoopy and the cast of characters evolved over the years.

In 1960, for example, Snoopy began to think his own thoughts and got up on his hind feet and began walking around. As for Charlie Brown, Schulz says he likes him for his kindness and gentleness. Not surprisingly, Schulz comes across the same way.

Ten years ago, I got the opportunity to write about Schulz for a monthly publication. Would he grant me the interview?

"Will it help you?" he asked. Yes, it would, so we did it.

Unfortunately, the magazine changed editors and direction in the interim and the piece never got published. I dug it out last week.

Titled "Happiness is a Warm Hockey Stick," it centered on Snoopy's Senior World Hockey Tournament held yearly since 1975 at the Redwood Empire Ice Arena in Santa Rosa. Schulz built the rink for the community and himself.

Schulz had been swinging a hockey stick since his childhood days when maternal grandmother Sophia Halverson played goalie at the foot of the basement stairs. Since he was an only child, she won the position by default.

"I like to think that she made a lot of great saves," Schulz said.

Talking about his comic strip, he said, "Sometimes I'll draw something I think is so funny, my hand really can hardly hold still, I'm having so much fun doing

it." Then, he added with a typical self-deprecating jab, "About once every five years."

Asked which of his characters he is, he said, "You have to be all the characters, otherwise you can't create them."

He summed up his life that day 10 years ago.

"It's my world," he said. "I would rather be at the studio on the good days when I have something good to draw than be out playing golf or tennis or hockey or anything. Just a normal day is what I like to have."

January 2, 2000

By Dan Hulbert

Cox News Service

ATLANTA -- His message begins, with perfect rightness, "Dear Friends" -- for who in the world doesn't feel like a close personal pal of Charlie Brown, Snoopy, Linus, Lucy and all the other pint-sized legends of "Peanuts"?

Today Charles M. Schulz bids farewell to his daily installments of "Peanuts" with the letter to readers, bringing to a close the half-century run of the world's most beloved comic strip.

But the "Peanuts" world won't close up shop. New Sunday strips will run until Feb. 13, when Schulz plans a final farewell. After that, newspapers will continue to run daily and Sunday reprints from the last 26 years.

And "Peanuts" characters will loom large as ever in a $1 billion-a-year worldwide empire of theme park attractions, videos, books and other licensed products (would you believe a chain of Snoopy Place restaurants based in Singapore?).

Still, the day-to-day narrative of "Peanuts," the ever-unfolding comedy (with streaks of high drama!) is done. For Charlie Brown, the yearning for the little red-haired girl will be forever unrequited; the successful football kick (with Lucy diabolically "holding") unconsummated. Schulz, 77 and receiving chemotherapy for colon cancer, has decided to give up the rigors of the strip in order to recover his health. Assuming the treatments are successful, he hopes to concentrate on select "Peanuts" projects.

Paige Braddock, a former Atlantan who is creative director for Charles M. Schulz Creative Associates in Santa Rosa, Calif. (the six-person studio that coordinates all "Peanuts" products), is in regular contact with Schulz at his California home and says that he is looking forward to writing screenplays for more "Peanuts" animated videos when his cancer treatments are complete. Already in production in London is "It's the Pied Piper, Charlie Brown," first of a series of new videos contracted with Paramount.

As for the reprints, they will commence in newspapers Tuesday with classic strips from as far back as 1974, a cut-off date stipulated by the cartoonist even though he's been drawing Charlie Brown and a few other characters since 1950. A spokesman for United Media, which syndicates the strip to 2,600 papers worldwide, explained that by 1974, all of the major characters - including Pig Pen, Peppermint Patty and Woodstock -- had been introduced, and the strip had basically achieved its current look.

"Mr. Schulz isn't as fond of reprinting his earliest strips, because his drawing style has constantly evolved," says Lisa Wilson of United Media. "For many younger readers, the '70s strips will be brand new. We hope that with these reprints we can cushion the shock of Mr. Schulz's retirement -- give people their daily dose of 'Peanuts' comfort and joy."

One of the people who lives for those injections is Sandy Norman, a homemaker who for the Christmas holidays decorated two rooms of her Rockmart home with ornaments and plush figures of Snoopy and Woodstock.

"What a cool yet classy dog," Norman said of the multiple-role-playing canine. "The 'Peanuts' characters may be retiring but I believe there is too much history around for them to fade away."

Jodi Goldfinger of Stone Mountain, Ga., saluted her longtime favorite, Charlie Brown, who "thinks he's a loser but he's not, because he keeps on trying no matter how often the 'kite-eating' tree chomps his kite. Thank you, Charles Schulz, for keeping the kid alive in all of us."

Mike Luckovich, Atlanta Constitution editorial cartoonist, says that one of the biggest thrills of his career was being asked by Sparky (as Schulz's friends call him) to advise him on the choice between two possible endings to a "Peanuts" strip. Schulz took the Atlantan's advice.

Luckovich said many of the nation's foremost syndicated cartoonists are conspiring to pool their talents and create "a very big surprise for Sparky" in late May, when he will be honored with the Milton Caniff Lifetime Achievement Award at the National Cartoonists Society Reuben Awards convention in New York. As recently as last spring, Schulz was spotted outside a convention hall, tossing a baseball with friends -- keeping in touch with the all-American wellspring of Charlie Brown's angst.

"Sparky's a very nice, gentle person, and some people may even think he's difficult to approach, because he's so shy," Luckovich says. "I think there's still some Charlie Brown in him, after all."

And a lot of Snoopy, too, perhaps. Like the shyest of humans, Snoopy never spoke, but he had a bold, colorful interior life that we could telepathically share by means of thought balloons. Like Snoopy, Schulz could play myriad roles in his own mind. Fittingly, it's Snoopy that we see in today's final "Peanuts" strip, mulling over the typewriter that's magically balanced on the peak of the doghouse roof.

It's a portrait of the artist as a young beagle, dreamily scanning the horizon, interpreting the clouds.

SCHULZ CHALLENGED US TO HURDLE LIFE'S OBSTACLES

January 2, 2000

By Paul Reid

Cox News Service

WEST PALM BEACH, Florida -- A self-portrait of Charles Schulz hangs above a doorway at the International Museum of Cartoon Art in Boca Raton. It's strange to see an adult drawn by Schulz - shock of white hair, soft smile, bright eyes, clearly a grown-up.

We have known his diminutive creations for almost a half-century, but we have not known the artist. He has been the invisible man who touched millions of lives with his gang of kids, a dog and a bird.

The portrait looks down upon a 50-years-of-"Peanuts" exhibit, Oct. 2, 1950, to Oct. 2, 2000. Below it is a computation of how many "Peanuts" strips Schulz will have drawn by Oct. 2.

18,236.

We'll have to settle for around 18,000.

Today, the "Peanuts" gang retires after almost -- but not quite -- 50 years.

Linus, Lucy, Charlie Brown. They were just kids 50 years ago, maybe age 8 or 10 or thereabouts. Now they're retiring. At age 8 or 10 or thereabouts.

And that dog. He's about 350 in dog years, and still waiting for a bowl of something other than dog food. Still waiting for a clean shot at the Red Baron. Today Snoopy, the Walter Mitty of dogdom, puts his Sopwith Camel into mothballs.

And his fine feathered friend. Today, Woodstock flies off to wherever 30-year-old birds fly off to.

WE WISH HIM WELL

Game's over. Charlie Brown's hapless baseball team leaves the field. Lucy kicks the football into a closet. The kite is treed for good.

Today, the Great Pumpkin looks for another magic patch.

And so do we.

Charles M. Schulz, 78, has capped his ink bottles.

Schulz, we hope, will beat the colon cancer that forced his retirement, will get to Oct. 2 and many years beyond. We wish him well because we feel we know him. We know we like him. And we love his creations.

But we're greedy, aren't we? We want him back, and he hasn't even left. We're like Linus on the morning after Halloween when, once again, there's been no visit by the Great Pumpkin: a little bit alone, a little bit sad, but ever faithful.

Maybe that security blanket Linus tugged around all these decades was Schulz's inside joke on us. His comic strip became our blanket, always there when we wanted it. Small, plain, homespun, but full of redemptive power.

That was "Peanuts." Big gift in a small package. Irony without cynicism. Wisdom without preaching. Humor as expressive and graceful as those bars of Beethoven that Schroeder pounded out on his miniature grand piano.

STORYTELLING WITH A LESSON

No adult ever appeared in the strip, yet this was anything but a strip just for kids. Schulz wound a double helix of humor around the "Peanuts" gang: Slapstick stunts kids loved entwined with nuanced jabs at adult pretensions that adults loved. A single strip, a single quizzical look on Charlie Brown's face, could carry two distinct jokes, two lessons, two stories. That's the genius of Schulz.

Give a kid and an adult a "Pogo" strip and the adult might laugh. The kid will be totally confused. Walt Kelly, Pogo's creator, was the Faulkner of the cartoon genre. Give a kid and an adult a "Daffy Duck" strip and the kid might laugh. The adult will furrow a brow.

"Doonesbury"? baby boomer laughs; grandparent does not. "Beetle Bailey"? Old G.I. laughs; Baby Boomer looks for "Doonesbury." Al Capp? A genius, but you won't find your 8-year old rolling on the floor.

But give anyone a "Peanuts" strip, and they'll find something to smile about. Nobody grabbed everybody like Schulz. Maybe that's why so many millions of readers turned to "Peanuts" before they read the day's dose of bad news. And why so many millions more turned to "Peanuts" as a balm after reading the day's bad news. There's nothing like Snoopy beholding a sunset to remind you, if only for a moment, of life's bounty.

Or take Sally, the girl who cannot fathom school, who reincarnates our childhood fears of teachers. Or Woodstock, named in 1970 for the rock concert, who became Schulz's metaphor for an entire generation: awe-inspired, curious, tentative in spite of its rhetoric. Pig Pen was the iconoclast, the rebel in Schulz. Linus is trust personified, but with a security blanket. Just in case.

THE GANG'S ALL SCHULZ

It's easy to forget that this gang is the emotional expression of a single artist. The "Peanuts" gang is Schulz.

He said once that Lucy's cynicism was his way of dealing with his own.

And Snoopy harbors Schulz's desire for adventure - Schulz grew up reading "Steve Canyon" -- and Snoopy takes flight where Canyon left off.

Charlie Brown a loser? Too easy. Charlie Brown is the common man, the everyman. He is Schulz's vehicle for coming to terms with the three years he spent in the Army during World War II.

"World War II taught me all I needed to know about loneliness," Schulz said in a memoir. "And my sympathy for the loneliness all of us experience has dropped heavily upon poor Charlie Brown."

Schulz gave us a window on his soul, as great artists do. And he gave us a window on our world, on ourselves, as the greatest artists do.

He once said that he hoped only to add something to the cartoon profession he loved. Boy, did he ever.

His gang of shorties taught us how to lose with grace. They taught us how to dream, share, discern. Snoopy challenged the Red Baron and the cat next door. Lucy challenged everybody. Sally challenged the establishment. Linus challenged faith.

Charlie Brown challenged life.

And Charles Schulz challenged us.

Now, the strip is going into syndication. Reruns. It won't be the same, will it? There's something very un-"Peanuts" about syndication. We'll be seeing ghosts, looking back. No matter how often his kite crashed, no matter how often his team lost, Charlie Brown never looked back, only up and onward.