VINCE GUARALDI

He worked for more than Peanuts

by Derrick Bang

This article originally began life as a shorter piece in the summer 1993 issue of the Peanuts Collectors Club newsletter; it has been expanded several times since then, and ultimately led to the publication of my book, Vince Guaraldi at the Piano.

No, our ears were not deceiving us.

The two Peanuts television specials, 1992's It's Christmastime Again, Charlie Brown and 1994's You're in the Superbowl, Charlie Brown, were highlighted by a welcome musical homecoming: Vince Guaraldi's original jazz themes, as interpreted by GRP recording artist David Benoit.

"Cartoon music," as it is pejoratively dismissed, rarely has been granted the respect it sometimes warrants. Like film soundtracks, the themes behind animated characters often are as invisible as the composers who penned them. To a certain degree, that omission is deserved; although Warner Brothers studio composer Carl Stallings filled Bugs Bunny and Road Runner cartoons with echoes of everything from Mozart to the frenetic noodlings of Raymond Scott, most folks think of cartoon music in terms of the vapid -- and overly enthusiastic -- vocal renditions of "Meet the Flintstones." A catchy title tune, cacophonous sound effects, and minimal interior melody.

(Just in passing, staunch fans of quality animation music should seek these three CDs: two volumes of The Carl Stallings Project, which feature themes, variations, and a few complete Warner Brothers cartoon soundtracks; and Reckless Nights and Turkish Twilights, which showcases the wildly original Raymond Scott compositions excerpted by Stallings. Scott was decades ahead of his time; you've truly never heard anything like this stuff before...except in just about every Warner Brothers cartoon ever made.)

All this changed when San Francisco jazz pianist Vince Guaraldi was hired to score the first Peanuts television special, a documentary called A Boy Named Charlie Brown (not to be confused with the big-screen feature of the same title). Superficially no different than any other television analysis of a noteworthy individual -- in this case, Charles Schulz -- the show nonetheless brought together four remarkable talents: Schulz, writer/producer/director Lee Mendelson, animator Bill Melendez and Guaraldi.

Somehow, the whole became greater than the sum of its parts.

Somehow, Mendelson never was able to sell the show to any TV network (and that's another story).

That hiccup aside, Guaraldi's smooth trio compositions -- piano, bass, and drums -- perfectly balanced Charlie Brown's kid-sized universe. Sprightly, puckish, and just as swiftly somber and poignant, these gentle jazz riffs established musical trademarks which, to this day, still prompt smiles of recognition.

They reflected the whimsical personality of a man affectionately known as a "pixie," an image Guaraldi did not discourage. He'd sport funny hats and wild mustaches, and display hairstyles from buzzed crewcuts to rock-star shags.

"You'd never know when you were going to recognize him," Schulz once commented. "Something was always growing or not growing."

But exactly where did Vince Guaraldi come from?

Flashback: Saturday evening, October 4, the penultimate evening of 1958's first annual Monterey Jazz Festival, the now legendary event founded by radio disc jockey Jimmy Lyons and jazz critic Ralph J. Gleason. It's after midnight, closing in on 1 a.m. -- "kind of early in the morning, late in the evening," as Cal Tjader commented, when he finally hit the stage -- and 6,000 rabid jazz fans have had their fill. The last meal was eons ago, the chilly ocean breezes and Monterey fog are cutting through even the warmest coats, and folks are ready to boogie home.

Who could blame them? They've seen and heard the likes of Dizzy Gillespie, Ernestine Anderson, Sonny Rollins and numerous other jazz greats. They know Billie Holiday will take the stage the following evening, Sunday. The sensory cup wasn't just full, it ran over hours earlier.

Few, as a result, would have envied the six youthful individuals who took the stage for their finale. Even Tjader, already earning the respect of his peers -- and already having performed earlier that evening -- must have been nervous as he assembled his combo. What could be worse than having folks walk out on you, at the Monterey Jazz Festival?

He needn't have worried.

Thanks in no small part to the "sound of surprise" from a feisty pianist named Vince Guaraldi, whose extended blues riffs literally had the crowd screaming for more, Tjader's band received more than a standing ovation. The group garnered the highest possible accolade: folks reluctantly departed -- only after festival officials killed the stage lights -- wanting to know where else they could hear these guys...and where to buy their records.

At this moment, Guaraldi was midway through the second of his two stints with Tjader.

Like most so-called overnight successes, Vincent Anthony Guaraldi -- who forever described himself as "a reformed boogie-woogie piano player" -- worked hard for his big break.

The facts are dull enough: the man eventually dubbed "Dr. Funk" by his compatriots was born in San Francisco on July 17, 1928; he graduated from Lincoln High School, served two years in Korea and then took classes at San Francisco State College, but did not graduate.

The music was the important part. Guaraldi began performing steadily after returning from his military service, haunting sessions at the Blackhawk and Jackson's Nook, sometimes with the Chubby Jackson/Bill Harris band, other times in combos with Sonny Criss and Bill Harris. He played weddings, high school concerts, and countless other small-potatoes gigs.

His favorite musicians included Bill Harris, Oscar Peterson, and Tal Farlow. "Jimmy Yancy was a great early influence on my playing," Guaraldi often explained. "Also Albert Ammons and Pete Johnson, but it was Yancy's way of handling the blues that really grabbed me."

One of his first serious bookings came at the Blackhawk, when he worked as an intermission pianist...filling in for the legendary Art Tatum. "It was more than scary," Guaraldi recalled, years later. "I came close to giving up the instrument, and I wouldn't have been the first after working with Tatum."

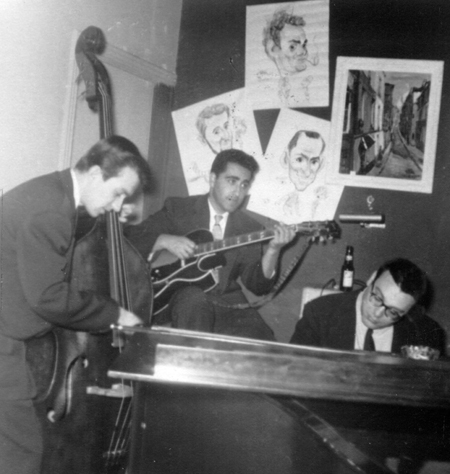

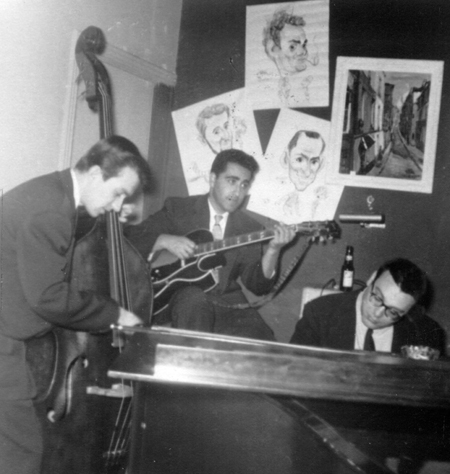

Guaraldi's first recorded work can be heard on The Cal Tjader Trio, a 1951 release and also Tjader's very first album for Fantasy. Guaraldi joined Tjader and bassist Jack Weeks for four tracks -- a pivotal 11 minutes of music -- that reveals, even at that young age, the soon-to-be-famous pianist's serious jazz chops. Although he and Weeks remained with Tjader until 1953 (when the latter was offered a job with George Shearing), Guaraldi then avoided studios for the next few years, preferring to further hone his talents in the often unforgiving atmosphere of San Francisco's beatnik club scene. In 1954, he put together his own trio -- longtime friend Eddie Duran on guitar, Dean Reilly on bass -- and tackled North Beach's bohemian hungry i club. (The lower-case name was an affectation, like so much of the "beat" era.) While luminaries such as Mort Sahl and Professor Irwin Corey headlined on the main stage, Guaraldi's group held forth in a smaller lounge appropriately dubbed "The Other Room."

Pretty soon, customers bypassed the main stage and headed straight for that other room.

(A few years later, Guaraldi became the hungry i's first jazz headliner. To nobody's surprise, his appearance was less a booking, and more an event.)

1955 saw his return to studio work. In addition to lending his keyboard support to the Ron Crotty Trio, Guaraldi made his recorded debut as group leader, although with different personnel: John Markham (drums), Eugene Wright (bass) and Jerry Dodgion (alto sax). All these cuts, two of them written by Guaraldi -- one of those, "Calling Dr. Funk," an acknowledgment of his already common nickname -- can be found on Modern Music from San Francisco (Fantasy, 3-213).

Guaraldi really honed his skills, though, when he renewed his working relationship with Tjader. Vince joined Tjader's working band in June 1956 and played countless club dates with these guys through January 1959.

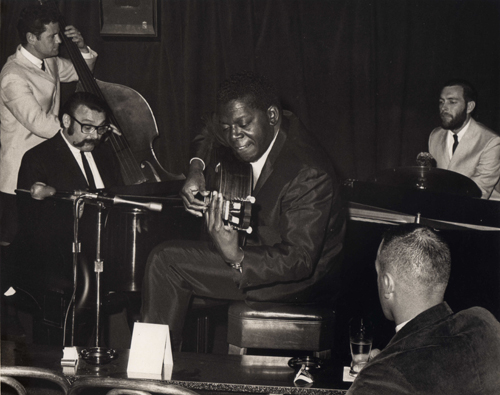

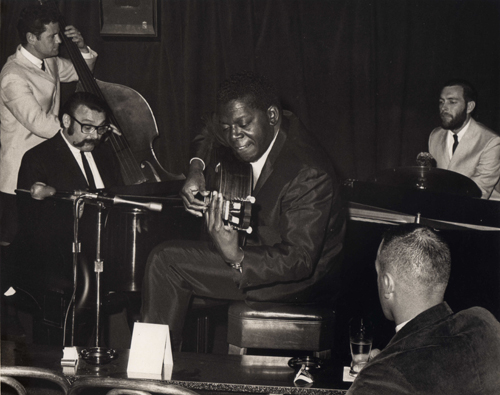

During these two-and-a-half years, Guaraldi was part of two different bands while associated with Tjader. The first featured Vince, Eugene Wright (bass), Al Torre (drums and timbales) and Luis Kant (congas and bongos). This group stayed together from June 1956, starting with Jess Cooley on drums; he was replaced by Al Torre in September that same year, and then that line-up remained fixed until March 1958.

At that point, Wright, Torre and Kant departed for other pastures -- on friendly terms -- and in April 1958 a new group featured Vince, Cal, Al Mckibbon (bass), Willie Bobo (drums and timbales) and Mongo Santamaria (congas and bongos).

This quintet, with special guest Buddy DeFranco on clarinet, is the combo that wowed the 1958 Monterey Jazz Fest crowd ... and their entire 36-minute set finally was released on CD in 2008 by Concord: The Best of Cal Tjader: Live at the Monterey Jazz Festival 1958-1980.

The basic quintet remained together until Guaraldi left in early 1959. (He was replaced by Lonnie Hewitt.)

Guaraldi also turned teacher, if only to a limited degree. Budding jazz pianist Larry Vuckovich studied with Vince and Patricia Tjader (Cal's wife) in the late 1950s. As it turned out, Vuckovich became Guaraldi's only student. (They remained friends until Guaraldi died, and played together on occasion.)

What soon came to be recognized as the "Guaraldi sound," however, resulted from several recording sessions with his hungry i buddies. The original Vince Guaraldi Trio, with Eddie Duran and Dean Reilly, can be heard on two genuinely pleasant releases: The Vince Guaraldi Trio (Fantasy 3-225, recorded in 1956) and A Flower is a Lovesome Thing (Fantasy 3-257, 1957).

The late 50s were a busy time. Aside from studio sessions with Conte Candoli (two albums), Frank Rosolino (one album), and Cal Tjader (at least ten albums), Guaraldi toured in 1956 and '59, the first time with Woody Herman's third "Thundering Herd," replacing Nat Pierce on piano for one season. Three years later, Guaraldi became part of Herman's Anglo-American Herd, which toured the UK for two weeks. These interludes produced three albums, although Guaraldi's contributions are hard to distinguish amid the full-blown fury of Herman's big-band sound.

National prominence was just around the corner. Inspired by the 1959 French/Portuguese film Black Orpheus, Guaraldi hit the studio with a new trio -- Monty Budwig on bass, Colin Bailey on drums -- and recorded his own interpretations of the haunting soundtrack music by Antonio Carlos Jobim and Luiz Bonfa. The 1962 album was called Jazz Impression of Black Orpheus (Fantasy 8089), and "Samba de Orpheus" was the first selection released as a single. Combing the album for a suitable B-side number, Guaraldi's producers finally ghettoized a modest original composition titled "Cast Your Fate to the Wind."

Fortunately, an enterprising Sacramento, California DJ turned the single over...

...and the rest was history.

Buck Herring and Tony Bigg, program director and music director (respectively) at Sacramento's KROY, began playing "Cast Your Fate to the Wind" every two hours. In Anatomy of a Hit, a San Francisco area-produced documentary made a few years later, Fantasy Records' Saul Zaentz quite frankly credits them, and KROY, with helping transform "Cast Your Fate to the Wind" into a hit.

"Cast Your Fate to the Wind" won the 1963 Grammy as Best Instrumental Jazz Composition. It was constantly demanded during Guaraldi's club engagements, prompting interviewers to ask if the composer ever tired of his most famous composition. Guaraldi always shook his head, choosing instead to view such requests as an affirmation of his popularity: "It's like signing your name to a check."

Suddenly, jazz fans couldn't get enough of Guaraldi. He responded with several albums during 1963 and '64: Vince Guaraldi: In Person (Fantasy 8352), with Fred Marshall on bass, Eddie Duran on guitar, Colin Bailey on drums and Benny Velarde on scratcher; The Latin Side of Vince Guaraldi (Fantasy 8360), with Marshall, Duran, Velarde (timbales this time), Bill Fitch on congas, Jerry Granelli on drums, and a supplemental string quartet; and Vince Guaraldi, Bola Sete & Friends (Fantasy 8356), with Marshall, Granelli and Brazilian guitarist Bola Sete.

The latter marked the first of several collaborations with talented Brazilian guitarist Bola Sete; subsequent team-ups occurred on From All Sides (Fantasy 8362) -- with Marshall, Granelli, Budwig and Nick Martinez -- and Live at El Matador (Fantasy 8371), with Tom Beeson, bass, and Lee Charlton, drums.

(One cut on From All Sides, called "Menino Pequeno Da Bateria," underwent a slight transformation and emerged as "My Little Drum" in A Charlie Brown Christmas.)

It should not be imagined, however, that Guaraldi spent all his time in studios. Aside from his ongoing club dates, he also had a rather improbable gig at the 1963 Stanford/Oregon football game. "The Stanford Band went on strike, and my trio filled in during the half-time goings-on. They had a monster hi-fi PA system, and you could hear my trio all over Stanford Stadium...it was wild."

Bassist Fred Marshall was part of that gig, and he remembers that the band -- including the piano -- was set up on a big cart and rolled out to the middle of the field at the 50-yard line. As "stadium rock," per se, hadn't yet become the fixture it soon would, Marshall reckons this to be one of the first times that so many people had the opportunity to hear live music in "hi-fi" sound.

"The sound was clear everywhere," Marshall recalls, "even to us at the 50-yard line...and, after the first eight bars, the place came apart...positively hair-raising!"

Guaraldi also was a recognized fixture on television, if only in the Bay Area. He and jazz critic Ralph Gleason documented the success of "Cast Your Fate to the Wind" in the three-part Anatomy of a Hit, produced for San Francisco's KQED-TV Channel 9; additional, Guaraldi and two different trios did a pair of Jazz Casual TV show for Gleason on the same network.

The most prestigious task, however, was yet to come. Even before Duke Ellington played San Francisco's Grace Cathedral, Guaraldi was hand-picked to write a modern jazz setting for the choral Eucharist. The composer labored 18 months with his trio and a 68-voice choir, and the result is an impressive blend of Latin influences, waltz tempos and traditional jazz "supper music." It was performed on May 21, 1965, Guaraldi working alongside Beeson and Charlton.

"I had one of America's largest cathedrals as a setting, a top choir, and a critical audience that would be more than justified in finding fault," Guaraldi recalled, on the liner notes for At Grace Cathedral (Fantasy 8367). "I was in a musical world that had lived with the Eucharist for 500-600 years, and I had to improve and/or update it to 20th century musical standards. This was the most awesome and challenging thing I had ever attempted."

Clearly, if Vince Guaraldi could write music for God, he could pen tunes for Charlie Brown.

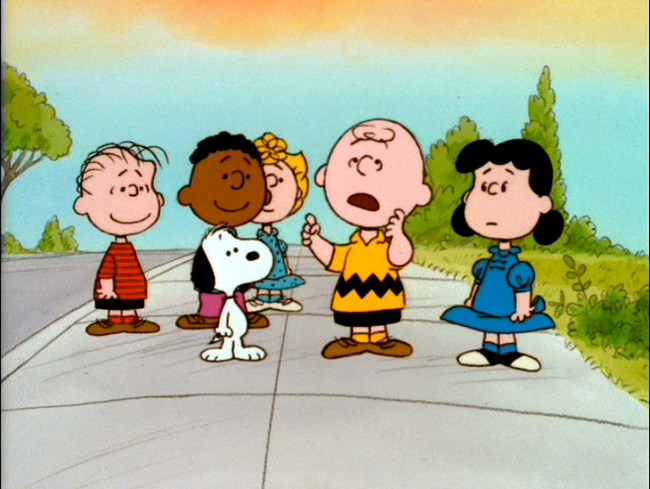

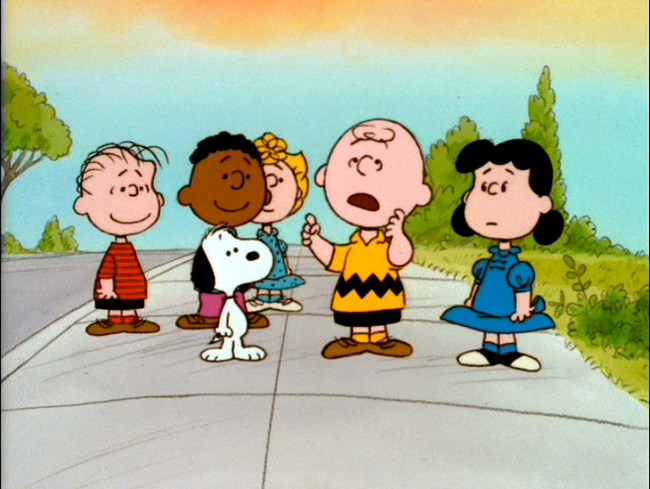

When A Charlie Brown Christmas debuted in 1965, it did more than reunite Schulz, Mendelson, Melendez and Guaraldi, who quickly turned the Peanuts franchise into a television institution. That first special also shot Guaraldi to greater fame, and he became irreplaceably welded to all subsequent Peanuts shows. Many of his earliest Peanuts tunes -- "Linus and Lucy," "Red Baron" and "Oh, Good Grief," among others -- became signature themes that turned up in later specials.

Guaraldi became so busy that the ensuing decade saw only half a dozen album releases, three of them direct results of his Peanuts work: A Boy Named Charlie Brown (Fantasy 8430), A Charlie Brown Christmas (Fantasy 8431) and Oh, Good Grief! (Warner Brothers/Seven Arts 1747).

Perhaps recognizing that the "Charlie Brown sound" bore more than a faint echo of "Cast Your Fate to the Wind," Guaraldi used familiar faces on the first two albums, to round out his trio...but exactly which familiar faces has been the subject of some interest for many years. Both original LPs failed to mention Guaraldi's sidemen in their copious liner notes, but the information did surface on Vince Guaraldi: Greatest Hits (Fantasy MPF-4505), released after his death, which credited Marshall and Granelli, respectively, on bass and drums.

Happily, the record was set straight when Fantasy re-issued the CD of A Charlie Brown Christmas, in August 1999. The first 11 cuts – which is to say, all the cuts from the original LP -- were made with Marshall and Granelli. The bonus track, "Greensleeves" (added when the CD version of the LP first was released), was made with Monty Budwig and Colin Bailey. (I’m indebted here to helpful information from Marshall himself, and his good friend Dorian Makres, who first called my attention to this matter.) Since these are two of Guaraldi's most popular albums, I can well appreciate the need to set the record straight...so let's hope the matter now can be set to rest!

Guaraldi's third Peanuts album, however, is quite unlike the others.

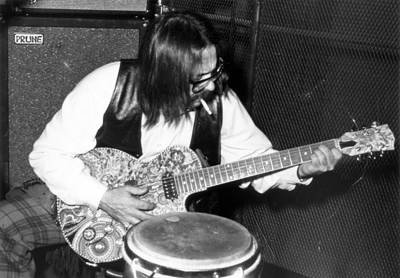

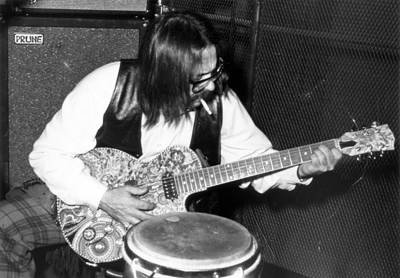

Indulging his own passion for experimentation, and acknowledging the by-now pervasive influence of rock 'n' roll, Guaraldi switched from piano to electric harpsichord and gathered Stanley Gilbert on bass, Carl Burnett on drums, and boon companion Eddie Duran on electric guitar. The results are far sassier and jazzier than his usual, quieter trio sound. Guaraldi even began playing guitar on occasion.

Between his switch from the Fantasy label to Warner Brothers, Guaraldi produced an album that has become quite obscure: 1967's Vince Guaraldi with the San Francisco Boys Chorus (D&D VG 1116). The mod jacket art and Guaraldi's mustached features were quite the counterpoint to a rather unusual album, which reunited the composer with the chorus that had accompanied him during several festival and concert appearances. Guaraldi's group included Duran on guitar; Beeson, Kelly Bryan and Roland Haynes on bass; and John Rae and Lee Charlton on drums.

Guaraldi's penultimate album, The Eclectic Vince Guaraldi (Warner Brothers/Seven Arts 1775), has several distinctions: aside from being damn near impossible to find, it marked Guaraldi's recorded vocal debut. (Mel Torme had nothing to worry about.) It also included one original composition, "Nobody Else," which sounded as though it would easily fit the Peanuts canon. This album featured quite the Who's Who of talent: Bob Maize and Jim McCabe on electric bass; Peter Marshall on bass; Robert Addison and Eddie Duran on electric guitar; Jerry Granelli and Al Coster on drums; and two celli, two violas and seven violins.

While undeniably scarce, that LP was practically common when compared to Guaraldi's final album. 1974's Alma-Ville (Warner Brothers/Seven Arts 1828) apparently received no more than token release. It was another ambitious album; in addition to old buddies Colin Bailey (drums), Monty Budwig (bass) and Eddie Duran (guitar), six other musicians were featured: Dom Um Romao and Al Coster on drums; Kelly Bryan on bass; Herb Ellis on guitar; Sebastio Neto on bass guitar; and Rubens Bassini on percussion. Of particular note was Guaraldi's guitar solo on one cut ("Uno Y Uno"), and Peanuts fans no doubt appreciated the appearance of "The Masked Marvel," a cut from the television specials that hadn't appeared on any other albums.

On February 6, 1976, while waiting in a motel room between sets at Menlo Park's Butterfield's nightclub, Guaraldi died of a sudden heart attack.

He was 47 years old.

I was midway through my four years at the University of California at Davis, a mere 90 minutes away from Guaraldi's favorite Bay Area nightspots. I'd long anticipated the thrill of one day driving over and watching him perform; I felt there was no reason to hurry.

And, as a result, I never made it.

A few weeks later, on March 16th, It's Arbor Day, Charlie Brown debuted on television. It was the 15th, and final, Peanuts television special to boast Guaraldi's original music. He had just finished recording his portion of the soundtrack on the very afternoon of the day he died.

Along with 1969's A Boy Named Charlie Brown -- the only big-screen Peanuts film to include Guaraldi's work -- these TV specials represent a legacy far weightier, even, than the few dozen albums carefully hoarded by discriminating jazz fans.

(Three decades later, no doubt responding to unceasing pleas from fans who wondered what had become of the themes and background music in all those other television specials, Fantasy released 1998's Charlie Brown's Holiday Hits -- FCD-9682-2 -- which included no fewer than nine previously unissued tracks, from the theme to A Charlie Brown Thanksgiving to a vocal rendition of "Oh, Good Grief," performed by Lee Mendelson's son's sixth-grade class. Although many of these "new" tracks are monaural and have the jump starts and quick fades of unsweetened television cues, the CD still is a gold mine for Guaraldi fans who spent 30 years repeatedly playing the first three albums. Suddenly, there were four ... and they've subsequently been supplemented by even more Peanuts music CDs, thanks to the efforts of Vince's son, David.)

Those who followed in Guaraldi's footsteps, on the Peanuts television franchise -- Ed Bogas, Desiree Goyette, Judy Munsen -- found the shoes impossible to fill. Not one produced a song or theme anywhere near as catchy as the Master, and several of the specials from the late 1970s and '80s consequently lacked a certain zip.

No doubt recognizing Guaraldi's invaluable contributions, Lee Mendelson and Charles Schulz paid him the highest possible tribute at the conclusion of The Music of America, one segment of the This is America, Charlie Brown miniseries. Responding to Lucy's doubts that he might actually have a favorite song, Charlie Brown replied,

"Well, there's one...and I think it was written in the 1960s. I think it was some of that jazz Franklin was talking about. I believe the composer was a man by the name of Vince Guaraldi. And I think it was called 'Linus and Lucy'...by coincidence.

"And I think it goes like this..."

...and he hummed the first few bars.

Cue the most familiar of all signature themes, which rose and enveloped the gang as they walked into the sunset.

Next to Linus' spotlighted explanation of Christmas in A Charlie Brown Christmas, this remains my favorite Peanuts three-hanky moment.

"I don't think I'm a great piano player," Guaraldi once said, "but I would like to have people like me, to play pretty tunes and reach the audience. And I hope some of those tunes will become standards. I want to write standards, not just hits."

He got his wish.

Solo pianist George Winston has played "Linus and Lucy" and other Guaraldi songs for decades, during his concert appearances. A promise to record it and other Guaraldi cuts finally bore fruit in the autumn of 1996, with the release of Winston's Linus & Lucy: The Music of Vince Guaraldi (Windham Hill 01934). In 2009, he followed that with a second album of Guaraldi covers.

Additional albums of Guaraldi's music have been released by jazz greats such as Wynton Marsalis, Dave Brubeck and David Benoit; no doubt the appearance of "Linus and Lucy" on the latter's This Side Up (ENP 0001) led to his selection as Guaraldi's ongoing torch-bearer. GRP Records had a smash hit with their soundtrack to the television special Happy Anniversary Charlie Brown, which gathered numerous jazz luminaries for their interpretations of classic Guaraldi compositions, along with some new cuts clearly inspired by Dr. Funk's Peanuts themes.

"Christmas Time is Here," recorded by luminaries such as singer Patti Austin, guitarist Ron Eschete and pianist Ellis Marsalis, is rapidly becoming a seasonal fixture. And damn near everybody of consequence has covered "Cast Your Fate to the Wind."

Let's fade with the words of Jon Hendricks, poet laureate of jazz, who once wrote:

"Vince is what you call a piano player. That's different from a pianist. A pianist can play anything you can put before him.

"A piano player can play anything before you can put it before him."

Notes:

Aside from Ralph Gleason's copious commentary on many Guaraldi albums, I'm also indebted to San Francisco Chronicle columnist John L. Wasserman's 3/15/76 tribute, and Ted Gioia's West Coast Jazz, for information found in this article.